Masseter Muscle Botox injections – the new clinical protocol

Masseter Muscle Botox injections – the new clinical protocol

AADFA International, outlines how to perform Masseter Botox injections that are compliant with the new clinical standard. This is the first in a series of articles drawn from Dr Holt’s recent presentations as the only dentist ever invited by the Australasian Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons to speak at their annual Non-Surgical Symposium.

There is no denying that the last couple of years have been challenging for everyone, with those challenges going beyond just the risk of contracting a new virus. The need to adapt rapidly and repeatedly to changes in life as we knew it, while dealing with the unique pressures of forced lockdowns and the increased stress that comes with a reduction or complete loss of income, have resulted in far reaching physical and psychological implications for a great number of people.

Dental practitioners across the globe have been reporting a dramatic rise in the rates and severity of manifestations like orofacial pain, TMD and bruxism. A study of more than 1800 people, from Tel Aviv University, found that people aged 35-55; women more than men; experienced the most significant rise in symptoms, with daytime jaw clenching increasing from 17- 32%; nocturnal bruxism increasing from 10-36%; and a 15% rise in symptom severity in people who had suffered from these conditions prior to the pandemic.

Over the past decade, Botulinum Toxin (Botox) injections, primarily targeting the Masseter Muscles, have become a proven front-line treatment option to address bruxism, TMD, jaw-clenching and resultant muscle hypertrophy. Yet, while Botox injections have a good safety and efficacy profile, they have not been without their problems. This article outlines the new clinical protocol for Masseter Botox injections that dental practitioners are now expected to follow, in order to maintain the appropriate professional standard; minimise risk; and enhance patient outcomes.

What was wrong with the old way of injecting Botox for Masseter Muscles?

The problem with the old way of injecting Botox was that it was a blind injection, based purely on presumption;

a practitioner’s generic knowledge of textbook anatomy; and largely unreliable physical palpation. Given the extreme variation and complexity of individual facial anatomy, injecting blindly is far from ideal, with research showing this issue of unpredictable, blind technique, being solely responsible for the occasional complications and poor clinical outcomes experienced from an otherwise safe and reliable treatment modality.

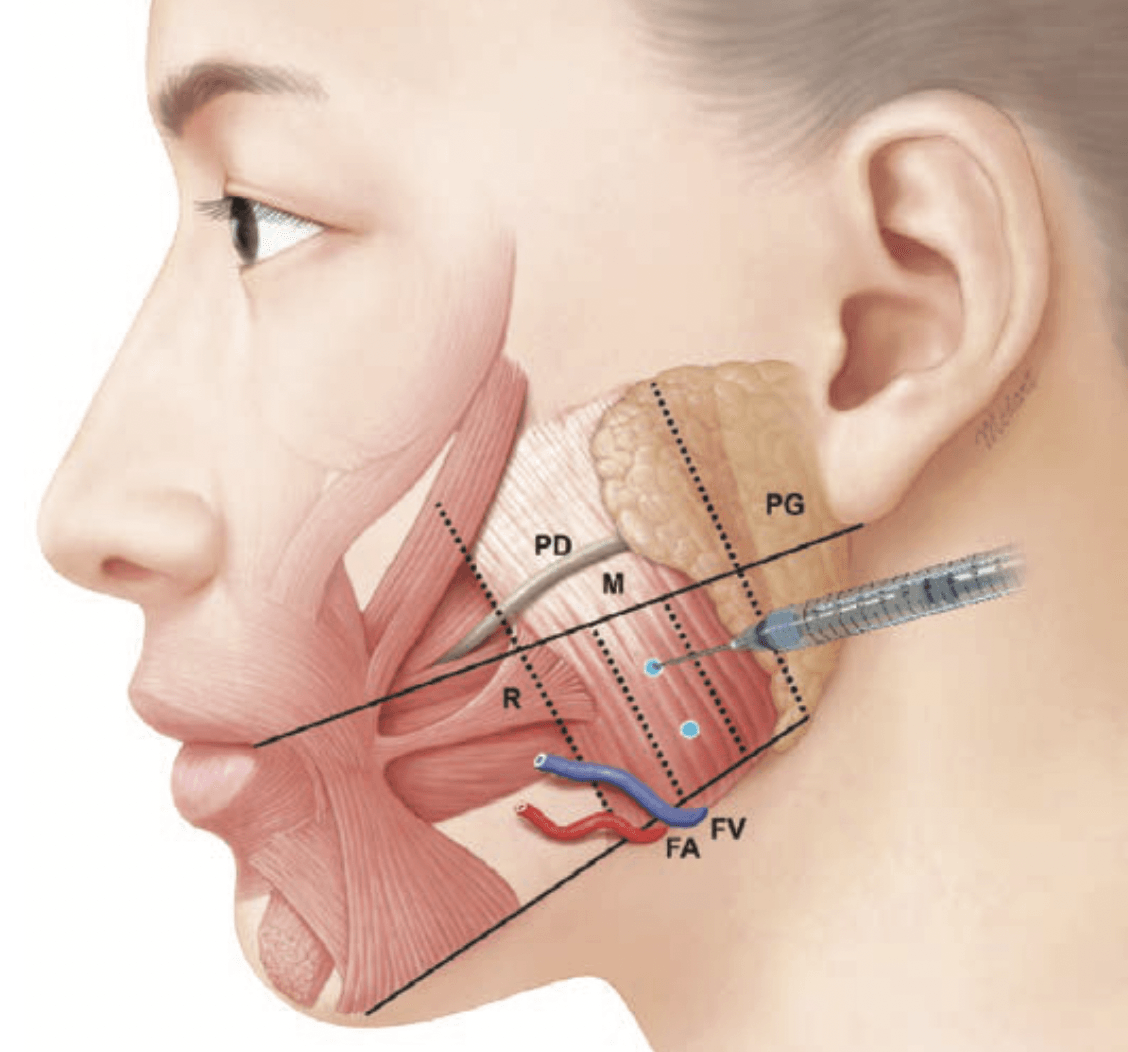

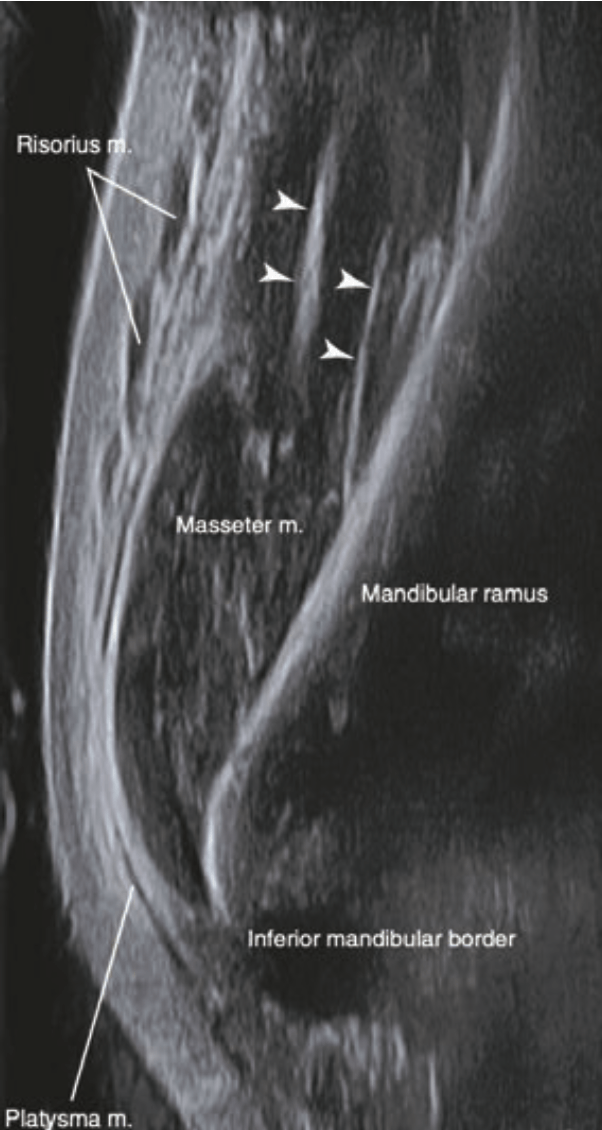

While the Masseter Muscle may seem like a uniform structure, its internal anatomy can be quite complex, while it also inhabits a position intimately entwined with several other key facial structures. It is a failure of the practitioner to be able to truly understand the individual anatomy of a patient’s Masseter, and how it interacts with structures like the Parotid Gland and Risorius Muscle, that has been shown to directly impact the safe and effective delivery of Botox injections.

Recent studies, using ultrasound, have shown that the old method for clinically selecting the site of proposed injection based on palpation and surface anatomy, showed a frequently erroneous location, with injection points in up to 40% of cases being placed too anteriorly, such that they were actually outside of the Masseter muscle altogether. In 20% of cases, it was shown that the needle selected for the procedure was too short to reach the deeper portions of the muscle, in certain individuals.

As a direct result of the limitations of a blind approach to treatment, three main iatrogenic side effects have been frequently reported following Masseter injections:

1. An asymmetrical smile (Fig.2)

The origin of the Risorius muscle generally covers the anterior third of the Masseter on the Superficial Musculoaponeurotic System (SMAS) layer. Injecting Botox too medially and/or shallowly, as has been shown to occur in up to 40% of cases, can result in the unintended paralysis of the Risorius muscle.

Studies show this to be the most common complication following injections to the Masseter, occurring in up to 27% of cases treated. The resultant unnatural or constrained facial expressions, most commonly a shortened, asymmetrical smile caused by reduced lateral extension, presents both functional and psychosocial issues for the patient and can last several months before returning to normal, as there is no active corrective treatment available.

2. Xerostomia

Cadaveric studies have demonstrated that up to 65% of individuals display anatomical variants of the size and position of the salivary glands compared to the generic textbook description. Inadvertent injection of Botox too laterally can impact the Parotid Gland, thereby reducing salivation and causing dry mouth – one of the reasons that Botox injections are now a frontline treatment for cases of Sialorrhea. The reported incidence rate for Xerostomia following Masseter injections is up to13%, and the recovery time is typically 3–4 weeks, with no active corrective treatment possible.

3. Paradoxical Masseteric Bulging (PMB, Fig.3)

PMB is the result of the injected Botox medication not diffusing evenly throughout the Masseter as intended, leaving active portions of the muscle to become hyperactive to compensate for areas of partial paralysis.

Occurring in up to 19% of treated cases, PMB creates isolated areas of unsightly muscle bulging when the Masseter contracts during mastication and other facial expressions/functions. While not painful or effecting normal function in any way, PMB presents considerable psychosocial issues for patients. Thankfully, this can usually be overcome using further targeted Botox injections into the areas of hyperactivity, though this presents the problem of having to use a higher cumulative dose of the toxin than would otherwise be needed.

Substantial research has clearly demonstrated that the anatomic reason for the occurrence of PMB is to do with the orientation and positioning of the Deep Inferior Tendon (DIT) of the Masseter muscle in any given individual, which prevents the Botox from dispersing uniformly during injection.

Furthermore, three distinct patterns of DIT positioning in relation to the muscle bellies of the Masseter have been shown to exist, with an even spread of about a third of patients having each variant. In order to ensure even drug dispersion and the avoidance of PMB, practitioners need to adopt a different pattern, location and depth of Botox injection, depending on which type of DIT arrangement exists. However, the traditional problem has been that it is nearly impossible to determine the internal location and arrangement of the DIT based simply on the appearance of surface anatomy or through palpation.

So, what is the new protocol?

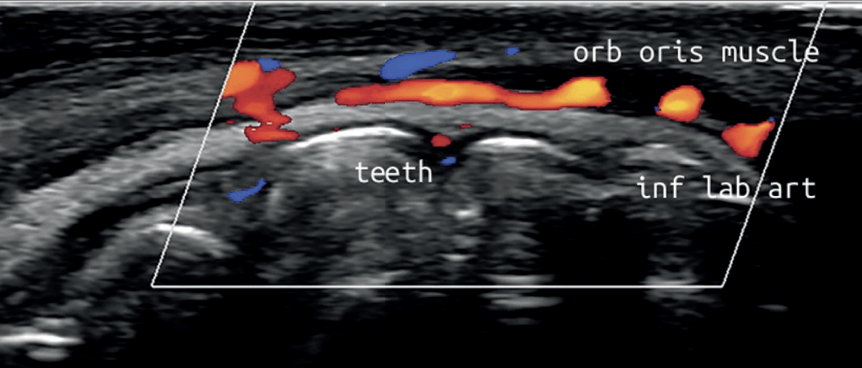

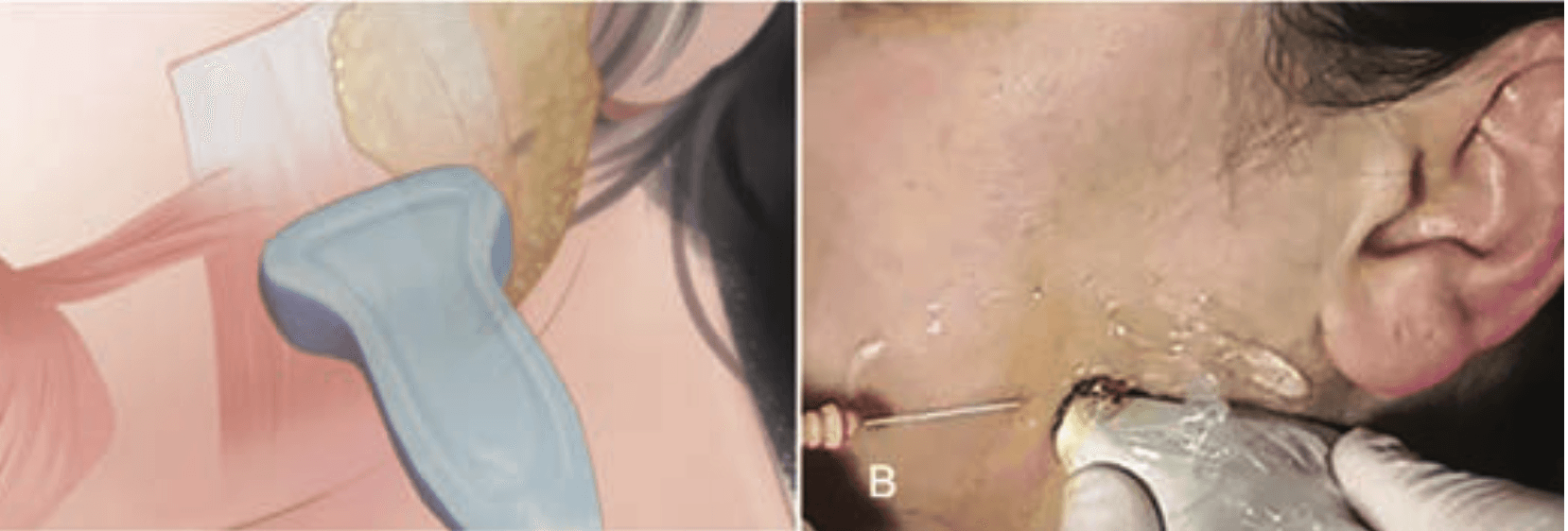

In line with the new regulatory and legal standards which are now in effect, dental practitioners are ethically and legally obliged to utilise the safest approaches to treatment available and to minimise risk. Portable, wireless, hand-held, ultrasound technology must now be used in the dental clinic to allow direct imaging of the Masseter muscle both before and during the injection of Botox, in the same way that dental x-rays are used routinely to diagnose; guide treatment; and avoid complications.

Practically, ultrasound must now be used by dentists looking to perform Masseter Botox injections in two ways:

1.

An ultrasound analysis must be recorded during the examination prior to performing the injections (Fig.5.). This allows the practitioner to evaluate the precise structural pattern of the DIT in each individual, as well as determining the exact location of the masseteric boundaries and the positioning of the adjacent Risorius muscle and Parotid Gland. From this pre-treatment analysis, an appropriate, individualized, injection plan can be developed in relation to the site; depth and dosage of Botox injections required.

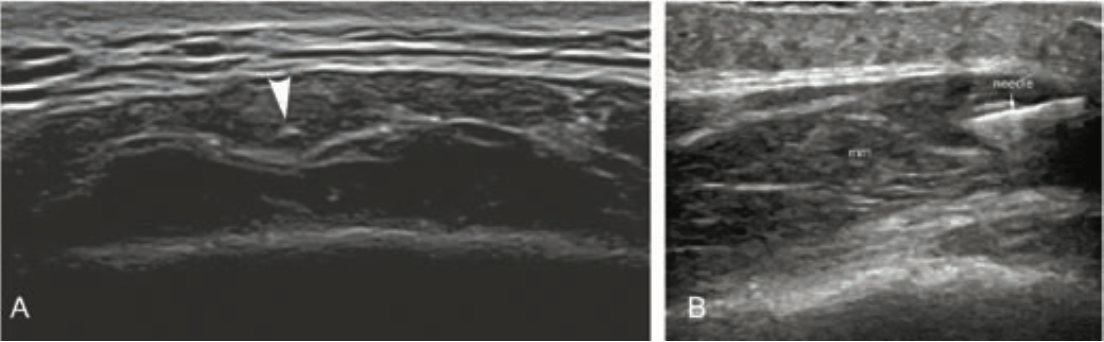

2. Ultrasound must then be used to actively guide the injection of Botox into the Masseter muscle, in real-time (Fig.6). Practitioners can avoid causing PMB, Xerostomia and asymmetrical smiles by directly visualising the injection process to target the correct parts of the muscle and avoid danger zones. Additionally, with the greater accuracy of injection afforded by ultrasound guidance, it has been shown that a significantly lower dose of Botox can be used to achieve the desired clinical result, further enhancing treatment safety.

What more do dentists need to know?

Until now, dentists had no other option but to inject Botox in a blinded fashion and this was the old accepted clinical standard which is now out-dated. In order to continue providing facial injections of Botox and Dermal Filler, dentists need to undergo a bridging course on how to utilise ultrasound protocols for increased safety and efficacy. As the use of ultrasound technology is not a regulated procedure, it is wise for dentists to ensure their assisting staff members are also fluent in the use of the technology, as this allows for greater clinical efficiency in practice.

A failure to utilise easily accessible imaging protocols would fall substantially below the level of care expected of a responsible dental practitioner and continuing to inject blindly would expose practitioners to regulatory action, and even patient litigation, should sub-optimal outcomes or complications occur, that could otherwise have been avoided. Additionally, a failure to disclose to patients that a method of visualisation exists which would make procedures safer and more effective would undoubtedly mean a failure to gain informed consent.

Practitioners who are unable to utilise ultrasound protocols for Masseter Botox injections, would now be expected to refer to someone who can.

For Guided Ultrasound Training in Facial Aesthetics, CLICK HERE to book.

Article references available from the author by emailing: clinical@AADFA.net